Happy Veterans Day to all of you who sacrificed so much to protect this country. Your efforts are deeply appreciated.

I’ve come to understand that verbally thanking someone for their service is the bare minimum of what I can do. Whenever possible, I like spending time getting to know veterans, their families and the stories they are comfortable telling. I also think that supporting veterans needs, even the ones they don’t say out loud are a huge part of thanking them for real. It took me a long time, maybe even too long to realize the latter when it came to my father. I wasn’t born yet when my dad went to Vietnam. I would say that I’m glad I missed that era, but truth is, I didn’t really miss it. How could I? It was a defining period in his life, which meant it would drive the type of parent, family member and spouse he would be. Serving in the Army during Vietnam would change him for the rest of his life and that means it would change all of our upcoming lives.

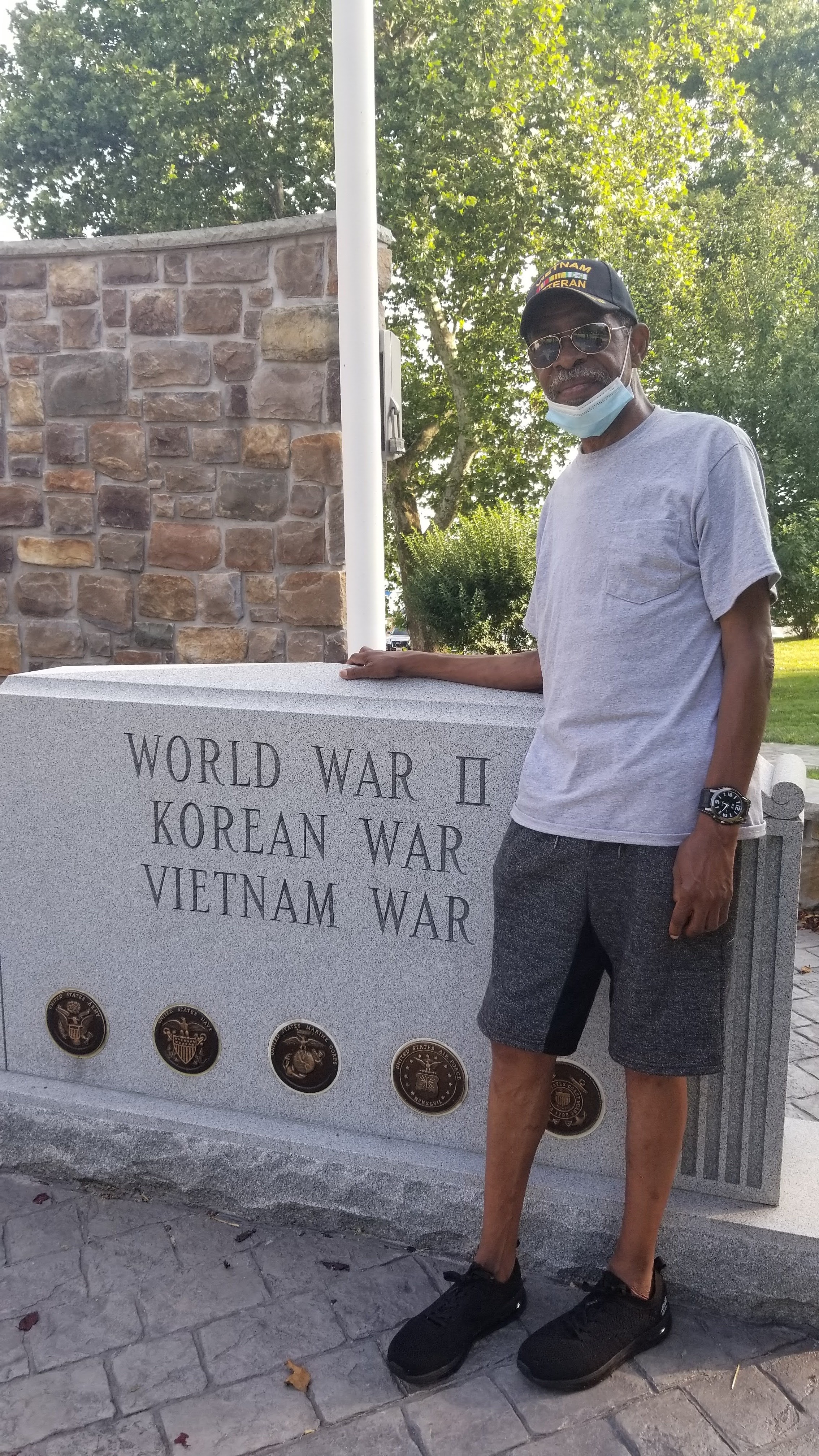

My father served in Vietnam from 1972 through 1975. He enlisted with many of his high school friends from his neighborhood of St. Albans, Queens, New York. While many young men may have enlisted, not many were lucky enough to return to their families. But what did it mean to be lucky to return? That sounds like a silly question doesn’t it? Who wouldn’t feel luck to be alive? Who wouldn’t feel lucky to be out of a war that citizens didn’t want us in to begin with? It took me a long time to fathom how these could be loaded questions.

When I was an psychology undergrad, I interviewed my father for a psych paper I had to write. I don’t remember the subject, but I remember the lessons I learned about offering grace and being tolerant during that interview. We discussed his time in the Army as well as some of his experiences in Vietnam. Growing up, we (my siblings and I) knew that he was in the military, but there was not much else he would tell us. We knew he drank a lot, but we didn’t know why. We knew he had nightmares and had a hard time sleeping, but we didn’t know why. We knew he was sad sometimes, but we didn’t know why. We knew he was very angry sometimes, but we didn’t know why. What we did know was that he was our dad and he was there. We felt his sentiment for wanting to be there. We did know that he cooked for us, did laundry, accompanied us on school trips, took us to the doctor, defended us fiercly and played with us. We did know that we loved to see him smile (he had a beautiful smile). We knew he hurt behind that smile, but didn’t know why and were too young to know to ask.

Back to our interview, which was over the phone. He was in New York and I was in Maryland. I’m sure he was on his made bed laying down, feet crossed at the ankle. Even though we were 200 miles apart, I could feel what he felt. As a “Defender of Mankind,” that can be heavy sometimes- feeling what other people feel so intimately. My father wasn’t exactly sober during that call, but he wasn’t several sheets to the wind, so we wouldn’t talk in circles, we’d get to it. He and his friends from the neighborhood he grew up in, St. Albans in Queens, New York, decided to join the fight. If 15 of them enlisted into the military from the old neighborhood, then only 3 or 4 made it back. That alone hurt his heart (survivor’s remorse). Some of these gentlemen were people he’d known since he was a small child. He was 18 when he enlisted. He talked slowly and deliberately about his experience. He spoke about having to send and receive communications (that was his expertise) with the threat of death right outside his location. He explained the stress and anxiety he and his troops felt every single day. He described people self medicating with alcohol (this is when he began drinking) and heroin. His voice trembled talking about the friends he’d lost during his time in Vietnam and although we were on the phone, I could see his face dampen. I could hear the tremor in his voice. I knew that his eyes glazed over as he allowed his mind to take him back to that time. I’d sat in my bed listening intently and being sure not to interrupt his thoughts. He recollected the blatant and ignored racism he experienced which raised his fear and anxiety levels even further. At times, he spoke directly to me and others, it seemed he was realizing that heartbreak all over again and at other times, I could hear him pull himself out of the haze and back to the present. I imagined he’d shake his head and wipe his eyes clear of the tears and come back to- as if I’d released him from his hypnosis.

I was writing a paper for psychology, so naturally, a few of my follow up questions involved treatment, resolutions, and what happened next? I already knew the answers to these questions, by having a front row seat to the peaks and valleys of his life. He said when he arrived back in the States, there were no reintegration programs. There were no mandatory psychological reviews. But did it matter anyway? They were taught to be tough. There’s no way a soldier would dare say out loud that he felt broken in any way- that would be displaying weakness. As it was, he talked about leaders not seeing Black soldiers the same as White- feeling they could endure more and not feel it. Even when I got older and realized the help my dad needed to come to terms with his experience, he didn’t know he needed it. I set up psych appointments with the VA because I just knew he had PTSD (shell shock back then), but anytime he sat in that chair, he’d say, “I’m fine. I’m not sure why my daughter made me come here.” I know there are plenty of men who served in Vietnam and were able to somehow overcome or compartmentalize their experiences, but there are so many who couldn’t. Couple the effects of war with being Black during that time and you’ve got a recipe for implosion.

There are so many stories I could tell regarding veterans I’ve met along the way, since having the realization that there are lasting effects of the things they were asked to do and to endure. I met a gentleman in a park one day. I was sitting on a bench writing another paper, kids not too far away on the playground. He sat on the bench across from me. He was much older than I and there with his granddaughter. I don’t even remember how we started talking about his time in Vietnam. I know it started out as friendly conversation. Conversation that I didn’t really want to have, I just wanted to write my paper, but I’m grateful I was there at that moment. A few minutes into our conversation, his face started to turn red and his hands started to tremor. His breaths and therefore, his sentences, were becoming shorter and more stagnant. He had long ago had my undivided attention- he needed it. He confided in me, a total stranger, that he still felt immense guilt over actions he had to take. He was given an order to fire upon an entity that he knew still contained his fellow soldiers, but more of the enemy. He followed that order and 40 something years later, he hated himself for it still. He realized he had to follow the order, but the ghosts of those men have never left his side. The guilt never left his side. He cried. Ugly cried. Right there. At the playground. In the middle of the day. I asked if it was ok for me to hug him, he just gave a nod and I did. A short time later, his granddaughter (who was happy as can be, had no idea of the pain her grandpa was in) came over and it was time for them to go. He thanked me for listening and they were off. I never got his name. I never saw him again, but I pray saying how he felt out loud helped him in some way.

I remember going with my dad to his appointment at the VA. There was a man sitting next to us. A bit after my dad went in, I made conversation, “Hi, do you ever attend any veteran events here or at a VFW or anything? Looking for some things I can help my dad get into.” His response floored me, although it probably shouldn’t have. He said something to the effect of, “Sweetheart, I go to my appointments and I go home and drink and wait to die.” Dad was out shortly after that. Of course I wanted to fix it, find out more, offer some hope. But I didn’t know him, his struggles, what he’d lost, who he’d lost. Instead, on the way out, I wished him the best and said a prayer for him everytime I thought of him, which was often.

It is great that we thank Veterans for their service. They endure so much that we (military allies and supporters) will never know about. There are struggles and challenges that us mere mortals may not survive. There are also lasting effects on the families that love and support these soldiers. They want to understand why their dad or spouse or child is not the same as when they left, but they may never really know. Whenever possible, it is imperative that we take any action possible to support these brave souls. Talk to a Veteran and just listen. Volunteer at the VA or another organization. Assist where you can with homeless veteran organizations. Just take action. The same goes for those Veterans who have made it through, fairly unscathed. We can still have conversations and we can still make things better because there’s always room for improvement.

If you are a Veteran and need help, please contact the Veterans Crisis Line.

Thank you Daddy for your service. Happy Veterans Day. I love and miss you.

-Just get out there and be dope-

AJDOM